When I say I'm weak for a good heist story, I mean weak. Ocean's Eleven, Locke Lamora, Holly Black's Curse Workers trilogy, The Sting, the list goes on. Give me a person (or, preferably, a group of people) robbing some rich asshole blind and having a snarky fantastic time while doing it, and I'll eat it up like candy.

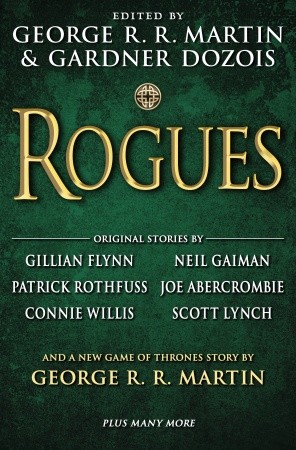

Greg Van Eekhout wrote a great blog last summer about the magic involved in a successful heist, and he's right-- there is something irresistible about that sleight-of-hand smile-at-me-while-my-partner-steals-your-wallet kind of character. As it turns out, George R. R. Martin feels the same way, and so he went about assembling a collection of stories all featuring rogues in one form or another. As with any anthology, this was a bit of a mixed bag, with some stories sticking more successfully to the theme than others. I've briefly reviewed each story in terms of its relevance to the theme, and its overall awesomeness, below the cut.

what started as a book review blog is morphing into a home for my musings on being a girl and being gay and the ways that intersects with my being a geek, and with geek culture. i do still and will continue to review books, because i read a lot and it's primarily what i enjoy talking about. if you've got a recommendation, or want to hear what i have to say on a topic, feel free to leave it in the comments.

22 January, 2015

13 January, 2015

cool shit i found to help you get over being forced to put on pants today

Because I know I'm not alone in being super, super bitter that I can't call out of work due to freezing my nonexistent balls off. Whether your balls manifest on this plane of reality or are entirely imaginary, I salute any and all of you who managed to drag them (and presumably the rest of your body as well) out into the world today.

Unless you live in Australia, in which case, go have an iced coffee and enjoy your warm weather somewhere I don't have to hear about it.

Some cool shit happened this week, like this Irish priest who came out to his congregation and got a standing ovation. That just warms the cockles of my freezing little heart, dammit.

On Sunday night, the Golden Globes was pretty great for women, with not only Their Royal Highnesss Tina and Amy calling out Bill Cosby for being a rapist on live TV (on Cosby's former home network, no less) but some really great roles for women, trans people, and minorities were handed out as well. Through a series of clicks I couldn't possibly retrace at this point I came across now-Golden-Globe-winning actress Gina Rodriguez talking about her role on Jane the Virgin and why cultural representation matters, which made me fistpump and say "Hell yeah!" Similarly, The Mary Sue pointed out how Bojack Horseman gets the whole representation thing too, which especially in light of last week's post about supporting characters in Disney films, makes me double fistpump.

(Also that show is hilarious and how come I'd never heard of it before last week??? Glad to have that hole in my media consumption filled in.)

Recently, on "Buzzfeed is a glorious timesuck that will simultaneously amaze you and ruin your life," they posted a collection of tumblr winning at the HP text post game. This not only gave me a chuckle, but sent me on this imaginative tailspin of planning an in-depth analysis of the ways fandom identity has shifted in its expression as the fandom community has shifted from LJ to tumblr. Like, how is our sharing of meta different, and graphics, and are memes the same, and how has the ubiquity of tumblr text posts allowed for shorter meta or headcanon sharing versus LJ meta which was often much longer... Yeah that's a dissertation I'm never going to write, but it's fun to think about. XD

Also, this week we learned that the secret to building the pyramids was a lot more prosaic than Fox Mulder and other theorists previously believed. (Sorry X-Men Apocalypse, you didn't get it right either.)

OK, that's all for this Tuesday. Stay warm, Northern Hemispherites, until next time!

<3

Unless you live in Australia, in which case, go have an iced coffee and enjoy your warm weather somewhere I don't have to hear about it.

Some cool shit happened this week, like this Irish priest who came out to his congregation and got a standing ovation. That just warms the cockles of my freezing little heart, dammit.

On Sunday night, the Golden Globes was pretty great for women, with not only Their Royal Highnesss Tina and Amy calling out Bill Cosby for being a rapist on live TV (on Cosby's former home network, no less) but some really great roles for women, trans people, and minorities were handed out as well. Through a series of clicks I couldn't possibly retrace at this point I came across now-Golden-Globe-winning actress Gina Rodriguez talking about her role on Jane the Virgin and why cultural representation matters, which made me fistpump and say "Hell yeah!" Similarly, The Mary Sue pointed out how Bojack Horseman gets the whole representation thing too, which especially in light of last week's post about supporting characters in Disney films, makes me double fistpump.

|

| it's a croc wearing crocs. meta game too strong... |

Recently, on "Buzzfeed is a glorious timesuck that will simultaneously amaze you and ruin your life," they posted a collection of tumblr winning at the HP text post game. This not only gave me a chuckle, but sent me on this imaginative tailspin of planning an in-depth analysis of the ways fandom identity has shifted in its expression as the fandom community has shifted from LJ to tumblr. Like, how is our sharing of meta different, and graphics, and are memes the same, and how has the ubiquity of tumblr text posts allowed for shorter meta or headcanon sharing versus LJ meta which was often much longer... Yeah that's a dissertation I'm never going to write, but it's fun to think about. XD

Also, this week we learned that the secret to building the pyramids was a lot more prosaic than Fox Mulder and other theorists previously believed. (Sorry X-Men Apocalypse, you didn't get it right either.)

OK, that's all for this Tuesday. Stay warm, Northern Hemispherites, until next time!

<3

12 January, 2015

Why I Am Charlie (and you are, too)

So, everyone has been talking about Charlie Hebdo lately, and I said a bit about it on tumblr last week after the debates started getting heated, and now after doing some more reading and thinking, I want to say some more.

I've never been personally attacked or threatened for my writing, but I know people who have been. It's not pretty. And while I acknowledge there's a very real difference between satirizing people or institutions with power and privilege at their command, and satirizing marginalized groups who are often the targets of random acts of hatred and violence themselves, the bottom line is that committing violence against people for speaking their minds is wrong.

John Scalzi's response to all this fervor hit the nail on the head. In talking about whether or not we agree with or support Charlie Hebdo's ideology, he says:

As artists, we have a responsibility to make the art we feel compelled to make. It might be snarky, offensive, racist, or just plain crap. But that doesn't mean we should be denied the right to make it, or that violence and murder is an acceptable response to art we don't like.

People have drawn parallels to Rush Limbaugh and asked if we would be defending him so hard if he'd been the one attacked for his hate speech. And as much as I hate to admit it, my answer is yes. I would rather be force-fed live slugs than do anything to support Limbaugh (I'm not even comfortable calling him an artist, but speaking your mind via film/music/graphics/writing and speaking your mind via rancid diatribes on the radio are not distinguishable in the eyes of the law, so the comparison stands). I loathe the man, and I wish he would come down with a case of permanent laryngitis or, you know, a lobotomy. But if someone were to murder him for speaking his tiny, bigoted mind, that would not be okay, and I would absolutely stand up in the street to protest that event.

Like Wendig says in his article about The Interview: protesting the things we find objectionable is part of social discourse. Threatening or enacting violence upon people for making or looking at art is fucked up and always, always wrong.

So yeah, #jesuischarlie. But whether you use the hashtag or not, you are Charlie too-- because you click links on Facebook, because you look at videos on YouTube, because you're reading this blog.

Because if murder as a response to art is okay, then that means we're giving governments and terrorist groups the power to decide what art is okay to make and what isn't. And if we go there, pretty soon the line between those who make the art and those who consume it is going to blur, and that's the start of a slippery slide.

It's simple: either free speech is protected or it isn't. If people are allowed to make films like Selma and Pride, to write Watchmen and put a gay wedding on the cover of an X-Men comic, then people are also allowed to draw racist cartoons and make terrible movies about assassinating Kim Jong Il and shout on the radio about the dangerous plague of gays in America.

We don't have to agree with Charlie Hebdo. We don't have to support their art or validate their points of view. But we can't lose sight of the fact that last week two men took 12 innocent lives because they didn't like some cartoons. And if we don't make it clear that we will not be silenced by terror, the person who uses guns as their first line of social discourse will never have any reason to put down the gun and try picking up a pencil instead.

I've never been personally attacked or threatened for my writing, but I know people who have been. It's not pretty. And while I acknowledge there's a very real difference between satirizing people or institutions with power and privilege at their command, and satirizing marginalized groups who are often the targets of random acts of hatred and violence themselves, the bottom line is that committing violence against people for speaking their minds is wrong.

John Scalzi's response to all this fervor hit the nail on the head. In talking about whether or not we agree with or support Charlie Hebdo's ideology, he says:

"my comfort level is about me, not about Charlie Hebdo or anyone else. Free speech, taken as a principle rather than a specific constitutional practice, means everyone has a right to share their ideas, in their own space, no matter how terrible or obnoxious or racist or stupid or inconsequential I or anyone else think they and their ideas are."Take, for example, the movie The Interview. The queens of comedy Fey and Poehler roasted it a bit last night at the Golden Globes, saying that the controversy forced us all to pretend we wanted to see it-- quite accurately, because I didn't want to, and still don't. But I was deeply unnerved by Sony's capitulating response to North Korea's threats. (Chuck Wendig did the best job of explaining why that should make us all nervous, in case you weren't already.)

As artists, we have a responsibility to make the art we feel compelled to make. It might be snarky, offensive, racist, or just plain crap. But that doesn't mean we should be denied the right to make it, or that violence and murder is an acceptable response to art we don't like.

People have drawn parallels to Rush Limbaugh and asked if we would be defending him so hard if he'd been the one attacked for his hate speech. And as much as I hate to admit it, my answer is yes. I would rather be force-fed live slugs than do anything to support Limbaugh (I'm not even comfortable calling him an artist, but speaking your mind via film/music/graphics/writing and speaking your mind via rancid diatribes on the radio are not distinguishable in the eyes of the law, so the comparison stands). I loathe the man, and I wish he would come down with a case of permanent laryngitis or, you know, a lobotomy. But if someone were to murder him for speaking his tiny, bigoted mind, that would not be okay, and I would absolutely stand up in the street to protest that event.

Like Wendig says in his article about The Interview: protesting the things we find objectionable is part of social discourse. Threatening or enacting violence upon people for making or looking at art is fucked up and always, always wrong.

So yeah, #jesuischarlie. But whether you use the hashtag or not, you are Charlie too-- because you click links on Facebook, because you look at videos on YouTube, because you're reading this blog.

Because if murder as a response to art is okay, then that means we're giving governments and terrorist groups the power to decide what art is okay to make and what isn't. And if we go there, pretty soon the line between those who make the art and those who consume it is going to blur, and that's the start of a slippery slide.

It's simple: either free speech is protected or it isn't. If people are allowed to make films like Selma and Pride, to write Watchmen and put a gay wedding on the cover of an X-Men comic, then people are also allowed to draw racist cartoons and make terrible movies about assassinating Kim Jong Il and shout on the radio about the dangerous plague of gays in America.

We don't have to agree with Charlie Hebdo. We don't have to support their art or validate their points of view. But we can't lose sight of the fact that last week two men took 12 innocent lives because they didn't like some cartoons. And if we don't make it clear that we will not be silenced by terror, the person who uses guns as their first line of social discourse will never have any reason to put down the gun and try picking up a pencil instead.

08 January, 2015

Disney made a mistake, but Emily Asher-Perrin didn't.

Earlier this week over on tor.com, Emily Asher-Perrin posted a thoughtful and, I thought, pretty spot on analysis of what Tangled, Brave, and Frozen all got wrong-- namely, that while they have female protagonists, they completely lack any female supporting cast, up to and including the animal sidekicks.

I know we're not supposed to read the comments, but I did. And after a lot of eyerolling, I came across one commenter who sparked a reply in me, which I'd like to expand on here.

The commenter wrote:

...why single out these three films when this happens EVERYWHERE. The critique really should be why does this happen (and everywhere, not just three Disney films, as in this essay here): one of the biggest selling genre series was written by a woman and it's a pretty white, male, heterosexual magical and muggle world that she's depicted.

And hey, that's not a bad question. Why target Disney, when this issue is disgustingly rampant and, let's face it, kids' movies are not even close to the majority of films that get produced in the US on a yearly basis?

It all comes down to how we critique, how we begin to frame the conversation. As I replied to that Tor commenter, an examination of the relegation of women to nameless windowdressing in all Disney films would be a dissertation, not a blog post. Lists help keep the discussion focused-- by critiquing these three films, Asher-Perrin isn't saying that they're the only films that need critiquing, she's using them as a jumping-off point to start a wider examination of the inherent sexism in Hollywood.

And boy, what a can of worms that is. The Huffington Post reported in 2012 that a study by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media that looked at nearly 12,000 roles in prime time TV, children's TV, and family films, "...[researchers] found a lack of aspirational female role models in all three media categories, and cited five main observations: female characters are sidelined, women are stereotyped and sexualized, a clear employment imbalance exists, women on TV come up against a glass ceiling, and there are not enough female characters working in STEM fields."

Ouch.

Let's take this a bit further. In 2013, the MPAA reported that the share of tickets sold to 2-11 year olds was at its highest point since 2009 (page 2), accounting for 12% of frequent (once a month or more) moviegoers (page 12). 7 of the top 25 grossing movies of 2013 were rated PG or under (page 23) with 4 children's films appearing in the top 10.

In a world where women account for only 28% of speaking roles in family films, that's a pretty strong message we're giving, over and over, to really young kids.

Studies show that kids learn a lot about gender roles and job expectations from media. If the TV tells them that 72% of people with important things to say are men, they're going to grow up thinking that's reality. If the TV tells them a 14 to 1 ratio of men to women in STEM fields is normal, they're going to internalize that as truth without even realizing it.

I say again: ouch.

The lack of adequate, varied representation of women in media is a big problem, one that reaches way further than Disney. But if we're going to critique, why not start there? Of course we want to erode entrenched sexism now, see more representation on our screens now. But it's also important to do whatever we can do to stop the cycle now, and give the next generation a chance to grow up without being spoon-fed so much subtextual sexism.

The point of Asher-Perrin's post was that if a juggernaut like Disney, who rakes in money even on its weakest offerings, were to start the ball rolling on equal representation, it might give other filmmakers (and artists, and writers) the courage to follow suit. The Tor commenter was wrong: Asher-Perrin's critique shouldn't be different from what it is, it should stand alongside and be considered intersectionally with critiques of other films, other studios, other media.

Her post is a gateway to a larger consideration of the kinds of movies and media we offer our kids, and especially in light of the Frozen fever that doesn't seem to be releasing its grip on America's kids (and adults!) anytime soon, I applaud her for getting the discussion started.

07 January, 2015

Cities, Planets, and a Partridge in a Pear Tree

Happy new year, everyone!

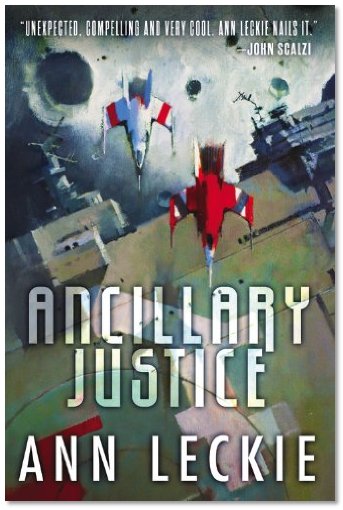

I don't know about you guys, but the holidays tire me out. December went by in a flash, and by the time New Year's rolled around I found myself lacking the energy to do anything but lie on my bed and read, in which pursuit I spent a glorious New Year's weekend. Immersed in the fabulous Ancillary Sword by Ann Leckie, and then by the various worlds presented in George R. R. Martin's Rogues anthology, I got to thinking a lot about worldbuilding.

For a speculative fiction writer, worldbuilding is one of the most important parts of structuring the story you want to tell. You have to find a good balance between giving the reader a complete picture of the world you've imagined, and giving them so much information that the story gets lost inside the encyclopedia you're dumping on them. It's really easy to fall down on either side of that line, and the authors who walk it best manage to deliver their worldbuilding so casually you barely realize it's happening.

In that vein, I compiled a list of a few of the best examples of worldbuilding in fantasy and sci-fi, both as a reference for myself as a writer when I find myself mired in the hows and whys of my worlds, and for everyone else to enjoy and hopefully add to.

the Imperial Radch series by Ann Leckie - I imagine it's really hard to find a way to explain "My main character used to be a ship with thousands of bodies all controlled by her AI, but now all but one of the bodies are dead and she has to pretend to be human." But Leckie manages to do just that, and to give her narrator a place within a detailed and politically complex sci-fi universe, without infodumping even once. Some might argue she errs on the side of obscurity, and there were certainly places at the beginning of the book where I was a little confused, but the picture comes together at a slow but steady pace, and the final product is seriously, seriously cool.

When Gravity Fails by George Alec Effinger - While the plot in this book isn't the tightest one might wish from a murder mystery, the worldbuilding is outstanding. The city of the Budayeen is so vivid I can picture it in my mind even years after having read the book, same goes for the technology and weapons described. It's a textured blend of a place, it feels real even though it's unmistakably full of sci-fi elements. This is a case where the world is built effortlessly through the narrator's voice, as he travels through the social strata of the city trying to catch a murderer; you don't even realize how much of the picture is painted in until you step back and look at it from a distance.

When Gravity Fails by George Alec Effinger - While the plot in this book isn't the tightest one might wish from a murder mystery, the worldbuilding is outstanding. The city of the Budayeen is so vivid I can picture it in my mind even years after having read the book, same goes for the technology and weapons described. It's a textured blend of a place, it feels real even though it's unmistakably full of sci-fi elements. This is a case where the world is built effortlessly through the narrator's voice, as he travels through the social strata of the city trying to catch a murderer; you don't even realize how much of the picture is painted in until you step back and look at it from a distance.

the Gentlemen Bastard sequence by Scott Lynch - This is my favorite book series being published right now, full stop. Lynch takes a fairly straightforward approach to worldbuilding, but he's clearly given his world an insane amount of thought, and there are just as many passages of description as there are casual allusions to things that help fill in the picture around the action. Camorr itself, the city setting of the first book, is like a Renaissance-era Venice if it were made by aliens and populated by the Mafia. But every city we've visited with Lynch, from Tal Verrar to Old Theradane, just straight-up feels like a real place. He knows just what details to give to make you feel the cobblestones under your feet and taste the wine on your tongue.

Dune by Frank Herbert - One of the greatest examples of sci-fi where the world is built through context. There's almost no info-dumping in Dune, just a lot of contextual allusions to important things that allow the reader to put together a complete picture of the worlds we visit. Like concentric circles, Herbert builds the Atreides family, the way they integrate with the Fremen society, the Fremen's place on Arrakis, and Arrakis's place in the universe, so casually you hardly realize he's doing it. Getting a POV on the Harkonnens, and the excerpts from Princess Irulan's writings, rounds out the bits we'd miss by sticking just with Paul's POV.

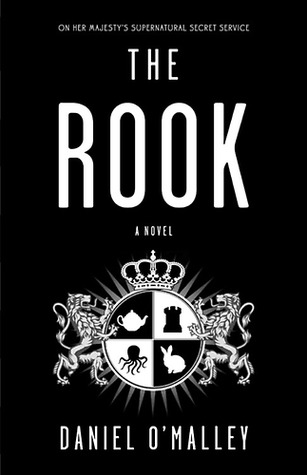

The Rook by Daniel O'Malley - In a story where your main character is a member of the British Supernatural Secret Service, coworker of vampires and dreamwalkers and sociopaths who inhabit four bodies at once, how to avoid the infodump factor? Easy-- make your character lose her memory and have to learn everything about her world all over again. I love epistolary fiction to begin with, and I really loved that The Rook is told half through letters from Myfanwy to her future memory-wiped self. Though there are sections that are heavy with information, it doesn't feel egregious because it's new to the character as well as the reader. Also, the inner structure of the agency is both brilliant and intuitive, so it's not hard to understand how the pecking order works.

the Harry Potter series - Similar to The Rook, a really great way to introduce your world to your audience is through the eyes of a character to whom everything is totally new. How better to ease us into the Wizarding World than by taking us, literally, to school there? It's pretty brilliant that Harry's new to being a wizard entirely, and not just new to the idea of Hogwarts-- his newbie status allows for continued worldbuilding throughout the series. My favorite use of this is probably in Book 5 when we learn about the Ministry's inner workings and St. Mungo's Hospital.

Any other examples of stellar worldbuilding you think I've left off the list? Shout 'em out in the comments, and I'll see you next time.

--emily

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)