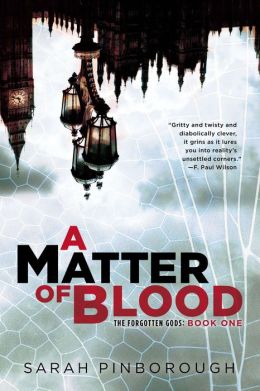

The opening act of Sarah Pinborough's urban fantasy horror trilogy is dark. It's gory, it's harsh and unflinching in its descriptions of an ugly world; no romps with city-dwelling fairies here. It's urban fantasy at its most brutal, illuminating a bleak potential future where-- as our killer makes a habit of pointing out-- nothing is sacred. It's that idea of the sacrosanct that winds its way throughout the book, touching each of the characters in turn, leading the jaded Detective Jones to a thorough examination of not only the ways in which his society is broken, but in which he is as well.

The book's jacket copy gives a pretty comprehensive summary: "London’s ruined economy has pushed everyone to the breaking point, and even the police rely on bribes and deals with criminals to survive. Detective Inspector Cass Jones struggles to keep integrity in the police force, but now, two gory cases will test his mettle. A gang hit goes wrong, leaving two schoolboys dead, and a serial killer calling himself the Man of Flies leaves a message on his victims saying “nothing is sacred.”

Then Cass’ brother murders his own family before committing suicide. Cass doesn’t believe his gentle brother did it. Yet when evidence emerges suggesting someone killed all three of them, a prime suspect is found—Cass himself."

I really enjoyed it, let's get that right out of the way-- it was gruesome and gritty and the characters were all deeply messed up in ways that made the twisty plot even more intense. It read like a Tana French book. I couldn't put it down. Lately I've gotten really tired of books that could wrap up in one installment, but whose authors seem bent on turning them into a trilogy just for the heck of it. This definitely isn't that sort of book. Sequels are necessary, and I'm mad I'm not reading them right now. There was just enough of the overarching big picture in the book to hook me like a gullible trout and leave me (pardon the visual imagery) flapping and gasping for more.

Maybe it's because my reading of A Matter of Blood coincided with my starting to watch the second season of Fringe on Netflix, but it got me thinking about the nature of scientific progress and its crossroads with that idea of sacredness. Most critics who have written about Fringe (which okay, is everyone) have talked about the show's central theme: the consequences of playing God, usually embodied by its semi-sinister mega-corp Massive Dynamic. In discussing its season 4 finale, the science/sci-fi blog io9 called it the "ultimate statement on scientific hubris", as Walter Bishop comes face-to-face with the outcome of his own scientific work being put to diabolical use by his one-time partner. And a 2012 article summed up Fringe's ethos nicely by saying "the use (or misuse) of any gift or ability begins in the heart, with all of its motives and emotions-- pure or otherwise." The show repeatedly highlights the line between reveling in the awesome power of science, and the dangers of pushing the boundaries just because you can. It also makes a pretty clear statement on what can happen when you do push those boundaries: even if you're careful, even if you have a damn good reason, ultimately when you mess with weird science like that, you can't control the results.

In A Matter of Blood, the way for paranormal chaos has been paved by the degeneration of society-- and when Pinborough talks about dissolution of a value system, she doesn't mean the kind that conservatives fear when they talk about gay marriage. As the first season of Fringe unspools into the second, the signs of Massive Dynamic's overarching influence get more and more pronounced, and it becomes clear that there is nothing they won't try at least once in the name of science. In Pinborough's world, law enforcement has lost its funding and policemen have to take bribes from career criminals in order to make a living. Every bank in Britain has been encorporated into the singular entity The Bank-- always capitalized-- a Massive-Dynamic-esque conglomerate that has its fingers in a lot of dirty pies. There is no sense of morality anymore, no lines of right and wrong that have not been crossed, just a listless focus on making life livable from day to day, even in the shadow of serial killers and the murder of children. What is sacred? Clearly our killer is right: nothing. But Pinborough's not just painting a terrible picture for her readers, she's warning us that if we're not careful we might inadvertently bring it to life.

The scariest dystopias for me are the near-future kind, the kind where I can clearly trace the path of how we got from here to there. Fringe teases out our fears about global warming, infectious diseases and other natural phenomena, and forces us to wonder what other nasty surprises science might have in store for us. Pinborough's future Britain, where everything is run by The Bank, plays on the paranoia of the CCTV culture and turns it up to eleven. How long will it be, we must ask ourselves, until Big Brother isn't just watching us, but controlling us? As the book's plot spirals downward, Pinborough lifts the veil on the rotten heart of this greed-fueled society, and it's truly an ugly sight. Solomon and Bright agree. Though their agendas differ, they seem to share the opinion that something must change. Mr Bright starts by appealing to people's inner decency, but ultimately he believes that they deserve what they get when they can't keep their word, when they place what other people think of them above the standards to which they hold themselves.

More subtly, it seems that not paying attention is an equal crime in the eyes of these enigmatic overseers. Cass is a good cop because he's unable to turn a blind eye to the necessities of corruption in his corrupt world, even as his choice not to see the Glow makes him unaware of that world's greater machinations until they start to contract around him. But I couldn't help seeing that self-chosen blindness differently. More than not wanting to be drawn into this rapidly thickening plot, Cass is content to be a cog in the wheel-- in other words, he doesn't want to play God. Not that dissimilar from Agent Dunham and her telepathic powers, which at first only manifest when her life is literally on the line. Both characters have lived in denial of their powers for decades. But could Cass have chosen not to see the Glow because he thinks he doesn't deserve it? His belief in his own brokenness is pretty apparent. In choosing not to see the Glow he's keeping himself free from the temptation of using his power for evil, but is he also hobbling his own ability to turn things around before it's too late? I fear the answer is yes, and given that the second volume in a trilogy tends to put the hero even further down before letting him rise, I am seriously afraid for what is going to happen to Cass in the next installment.

A last note on voice: Cass's narration is part of what made the book so enjoyable for me. I love noir, and as a narrator Cass's view on his world took on that same jaded, seen-through-a-haze-of-LA-smog-and-gin (or in this case, London fog and cocaine) atmosphere as some of Marlowe's stories. And like the classic private eye, Cass not only operates in a very lonely world, but struggles with his own painful past getting in the way of his ability to do his job. Luckily, he's made of sterner stuff than he knows. The division between his job as a cop and the more ephemeral destiny awaiting him as heir to the Glow and sole protector of his lost nephew is one that has only begun to show itself, yet Cass's strength of character is at the heart of both. Self-destructive, abrasive, emotionally cowardly he might be, but Cass has steel in him, tempered and true. In the way of the old adage, much has been given him, and I anticipate he's going to have a lot of expectations put on him from here on out-- and a mountain of guilt and grief to surmount before he can hope to

live up to them.

This is definitely not a book for someone with a weak stomach (or an aversion to bugs), nor is it likely to satisfy people who like lots of creatures and magic in their urban fantasy. It wasn't perfect; at times the foreshadowing was a bit clunky, and I had figured out Cass's dark secret long before it came to light on the page. But where it counts, the book delivered: it is a truly twisted mystery with an unpredictable conclusion that left me-- as I said-- no less than desperate for its sequel.

Almost as desperate as I am to head home today and pull up season 3 of Fringe on my Netflix queue.

No comments:

Post a Comment